Ghosts of racetracks past: A smile and an eighth at Atlantic City

Riders up at Atlantic City in 2013. Photo by Teresa Genaro.

by Linda Dougherty

“Atlantic City will always be special to me,” says veteran trainer Mark Reid, who was among the leading trainers at that now-shuttered racetrack in the mid-1980s. “It was the first racetrack I ever went to. When I was in college, my father said, ‘I’ll take you somewhere that’ll change your life,’ and we went to Atlantic City. And he was right: it was love at first sight for me, and I’ve been in this game ever since.”

They called it “A Smile and an Eighth.” Sometimes it was known as Hollywood by the Sea.

There were — at times — casino dancers working as hotwalkers on the backside, and on the frontside, all manner of celebrities ate, drank, socialized, and gambled. It was a different kind of place in a different time.

Atlantic City Race Course, located only a few miles from the New Jersey shore town that bears the same name, lifted the curtain on its first season of racing in 1946 with an all-star cast of original stockholders in attendance. Bob Hope, Frank Sinatra, and several of the nation’s big band leaders – Kay Kyser, Henry James, Xavier Cugat, Sammy Kaye and Axel Stordahl – had believed enough in the new racetrack being built in the South Jersey pines by former Olympian rower and politico John B. Kelly, Sr. that they eagerly invested in his project. Little did they know that it would be a box-office smash for several decades.

But eventually, Atlantic City fell victim to a combination of factors, limping to an ignominious death after the 2014 season under different – and largely indifferent – ownership.

Kelly, who owned a successful brickwork company in Philadelphia, constructed Atlantic City at a cost of more than $3.5 million. It was a unique mile-and-an- eighth track – hence the nickname — no less than 100 feet in width at any point, and made up of soil collected from local farms within a 10-mile radius. That soil was finely sifted and treated with white alba and, when laid over the circumference of the track, was very bright. The property also featured a half-mile training track, which abutted the barn area.

What was originally to be called the “Atlantic Pines Track” (the name Atlantic City Race Course was officially adopted in 1949) opened on Monday, July 22, 1946 to a crowd of over 28,000, and was hailed as the “racetrack of the future.” The clubhouse, described by one local paper as “up to the minute in design,” sported four elevators, a restaurant that seated up to 100 people, a barber shop, telegraph office and a two-story press box providing “unsurpassed communications” around the nation. Picturesque views of the surrounding pinelands, which encircled the track, could be enjoyed from the open-air grandstand.

The winner of the first-ever race that day was Christiana Stable’s Oberod. When the last race of opening day had been run, the total handle was $1.38 million on eight contests.

The inaugural season of racing lasted 24 days and produced an average daily crowd of 15,617, who wagered an average of $1.3 million. The track didn’t need much advertising in order to lure big crowds; a typical day saw racegoers standing elbow-to-elbow on the track apron, jostling for position in order to view the horses coming onto the track through the tunnel that ran underneath the grandstand from the paddock, as well as to see the race itself.

Ghosts of racetracks past

For the mid-Atlantic tracks that did not survive, all we have left are grainy photos, yellowed programs and tattered tickets, fading mementos of a time when big crowds and great horses reigned supreme. Their stories:

“Hollywood by the Sea”

Through the years, Kelly’s famous movie star daughter Grace Kelly was a frequent visitor, and, after she was married to Prince Rainier of Monaco, the pair were often seen there, even making trophy presentations in the winner’s circle.

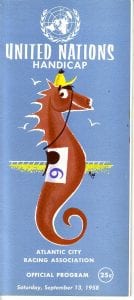

Program for the 1958 United Nations at Atlantic City. Courtesy of Linda Dougherty.

So many movie and television stars frequented Atlantic City in its first two decades of racing that it was dubbed “Hollywood-by-the-Sea.” Racing fans rubbed shoulders with Phyllis Diller, Jerry Lewis, Willie Mays, Ed McMahon, opera singer Anna Mary Dickey, comedians Block & Sully, the original members of Sinatra’s “Rat Pack,” and singer Dinah Shore. Former President Dwight D. Eisenhower made an appearance in August, 1965.

A key moment for the shore oval came on August 28, 1948, when turf racing debuted over its newly-installed mile grass course. At the time, its surface and engineering were hailed as the best of any in the country. Beginning in 1953, the track created what became one of its enduring legacies, introducing the United Nations Handicap, which brought together the best foreign and domestic turf horses and became, with Laurel Park’s Washington, DC International Stakes, the model and forerunner of the Breeders’ Cup World Thoroughbred Championships.

The United Nations quickly became one of the elite grass races in the country, with its list of winners a virtual “Who’s Who” of American turf champions. They included Round Table (1957, 1959), T. V. Lark (1960), Mongo (1962-63), Assagai (1966), Dr. Fager (1968), Hawaii (1969), Fort Marcy (1970), Tentam (1973) and Halo (1974).

Atlantic City could also boast of being the site of Horse of the Year Kelso’s first career victory, on September 4, 1959.

“A stake through the heart”

After Kelly died in 1960, he was succeeded as president by Dr. Leon Levy. A dentist by training, Levy was an early investor in Philadelphia broadcasting, and his WCAU became a leading radio and television property in that city. His wife was Blanche Paley, the sister of William Paley, the CBS kingpin. In 1966, Levy’s son Robert P. (Bob) Levy became track president, while Levy became Chairman of the Board of the Atlantic City Racing Association. Bob Levy would remain the president for the next 20 years.

Under Bob Levy’s stewardship, many capital improvements were made to the plant, including a fully enclosed Turfside Terrace Dining Room, a lawnside Beer Garden next to the paddock, instant replay magnetic tape closed circuit TV, and new jockeys’ quarters. The track was also an industry leader: the first to offer full-card simulcasting, and the first track in the state to offer night racing (in 1976, a few months before the Meadowlands opened). Levy created the Matchmaker Stakes in 1967, which awarded the first three finishers a breeding season to a trio of top stallions – Round Table, Hail to Reason, and Jaipur. Politely took the first two runnings of the Matchmaker.

Atlantic City even presented harness racing. In 1968, Ralph Cornell and Harry Holloran leased land from the thoroughbred group and spent $1.7 million to construct a five-eighths of a mile lighted harness oval inside the main track. The harness season ran from May through July, prior to the start of flat racing, and proved so popular with horsemen that 3,000 applications were received for 1,000 stalls.

The next year, the track hosted the Atlantic City Pop Festival, a three-day rock festival that attracted 111,000 paying customers (and several thousand additional freeloaders).

By 1970, the glory days of Atlantic City were all but over. New Jersey was moving towards a year-round racing calendar in an effort to reap more pari-mutuel tax revenue, with Monmouth Park, Garden State Park and Atlantic City each running 60 days, as well as the new Meadowlands. In 1976, voters in New Jersey drove a stake through the McKee City oval’s heart when it approved casino gambling and ushered in the Atlantic City casino industry, with the first casino opening in 1978.

“Atlantic City wasn’t like other racetracks”

When the 1980s dawned, stakes races and allowance races were replaced by cards of cheap claimers; purses dropped, and Monmouth Park and Atlantic City were now running an overlapping schedule, competing for horses and dollars. Yet many trainers loved to summer at Atlantic City, despite the low purses.

Reid, the trainer whose life changed with his first visit to Atlantic City, was one of them. A force on the Jersey-Pennsylvania circuit for many years, he looked forward to his annual vacation at the Jersey Shore while still training and racing his horses. Reid said that most years he was stabled in a long barn in a quiet area near the road, and called it “a great place to race.”

Postcard of Atlantic City Race Course courtesy of Linda Dougherty.

“I’d get a house in nearby Brigantine with the wife and kids,” said Reid. “I’d train in the morning, take the kids to the beach, take a nap, get up, maybe do some barbequing, and then race at night. Sometimes I’d go to Bally’s (casino) and lose everything I’d won at the track, but it was a glorious thing, and so much fun.”

Oftentimes, Reid would hire dancers at Bally’s to hotwalk for him, no doubt attracting plenty of attention to his barn at the crack of dawn.

“Atlantic City wasn’t like other racetracks,” he said. “I have a lot of great memories of it, and it’s one of the top tracks I’ve ever raced at.”

Another trainer who has fond memories of Atlantic City is J. J. Graci, who won a record four consecutive training titles at ACRC. Graci said he used to bring 50 head of horses into Barn W to start the meet, and would have 50 more on his farm in Mays Landing, just a few miles away. He said one of his best horses to race at the track was Reliable Jeff, who broke his maiden there on July 4, 1983, then went on to win multiple races at the track through 1987.

“Bob Levy told me he wanted to start simulcasting, and I said, ‘You mean to tell me people will watch races on television?’” Graci recalled. “He said yes, and I said, ‘What are you drinking?’ But at the time, nobody knew how big simulcasting would become. Bob was right.”

Graci said that, like Reid, he’d go to the beach during the day, and race at night.

“I wish Atlantic City was still running,” he said. “It was the best racetrack and had the best turf course in the country.”

The track struggled along, still running its summer meets in the 1990s, and in 2001 was sold to Greenwood Racing, which also owned Philadelphia Park in Pennsylvania. Under Greenwood, the track’s dates were slashed to six or seven per year – enough so that Greenwood qualified to conduct simulcasting year-round – and were run on turf only, as the main track was not maintained. Despite strong crowds turning out for the brief “turf festival” each spring – topping 13,000 on one 2013 occasion — Greenwood saw no value in expanding the number of dates, or making any capital improvements.

Essentially abandoned, the property fell into disrepair. The backstretch soon resembled a ghost town from a black-and-white Western movie, complete with tumbleweeds, swirling tornadoes of dust, and dilapidated barns replete with rodents. In the grandstand, groundhogs lived where movie stars once frolicked. By early 2015, Greenwood announced Atlantic City was closing for good.

The grandstand still stands today … a decrepit, crumbling monument to the glory days of thoroughbred racing in New Jersey, when crowds were big, the money flowed, and the good times never seemed to end.

I absolutely loved this article. I was trying to describe the Atlantic City Racecourse and all its splendor to a friend of mine. Now she knows. I have known Mark Reid along time and enjoyed his input. Thank you.

Thank you for the wonderful memory. It was the track of my youth.

In the early 80s, waiting tables at the beach in Wildwood NJ would spend my night off to hit ACRC Night Racing. What a gorgeous track and turf course. Would love seeing MD shippers especially when Mario Pino came up to ride. Sweet memories of ACRC. Thanks Teresa for helping me relive it.