Ghosts of racetracks past: Bowie and its breed

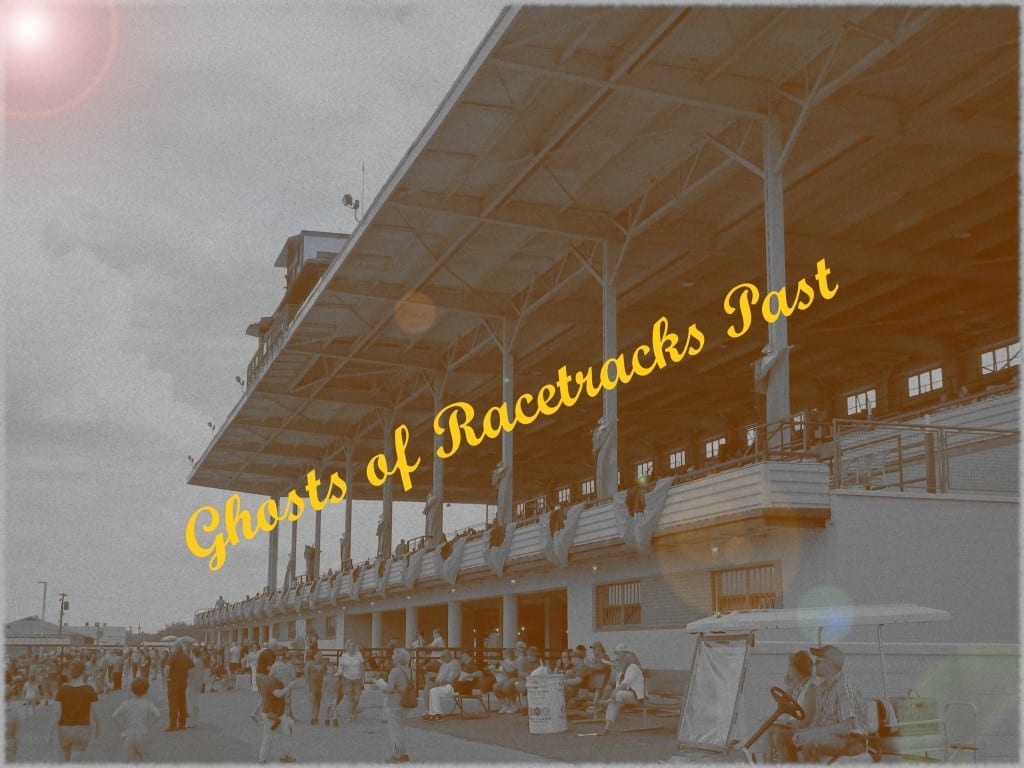

Bowie during live racing.

by Doug McCoy

They always remember the cold.

Ask trainers, jocks, even horseplayers, what they remember about Bowie Race Track, and in the end, it always comes back to the bitter cold and sudden storms at the track in the pines, which was the first East Coast venue to offer winter racing.

“About all you could do to deal with the cold was layer up clothing like turtlenecks and mud jackets and keep exposed skin to a minimum,” remembered retired jockey Chris McCarron, who got his start at Bowie. “We were given one pound leeway as to assigned weights, and that was about what a turtleneck and mud jacket weighed. Some riders, like Jimbo (Vince Bracciale, Jr.), would put baby oil on and that gave them some insulation.

“I used to wear two pair of gloves, a pair of leather gloves first then a pair of cloth gloves on the outside. Then when I got to the gate, I would take the cloth gloves off and stuff them in my silks. And we wore a hood like a ski mask, which covered everything but the eyes. But it was still pretty damn cold and pretty tough conditions to ride in!”

McCarron said while the added clothing restricted movement, once the race began riders forgot about those problems.

“Once they sprung the latch, you were riding and you didn’t think about the cold or anything else,” he remembered.

McCarron won more than 7000 races, two Kentucky Derbies, five Breeders’ Cup Classics, and two Eclipse Awards in a career that earned him a spot in racing’s Hall of Fame in 1989.

But back in 1974, he was living in a tack room on the Bowie backstretch, working for legendary horseman Odie Clelland, and counting the days until he could ride his first race.

“I was working for Odie, which meant you did everything: gallop horses, rub horses, whatever he wanted you to do, you did,” McCarron reminisced via phone from his home in Kentucky. “I can remember going to sleep at night to the sounds of the tractors passing by as they harrowed the track through the night.”

McCarron accepted his first mount on January 24, 1974 for Clelland, a non-descript claimer named First Active. “He couldn’t run a little bit,” McCarron recalled with a chuckle.

A couple of weeks later, on February 9, the rider won the first race of his career at Bowie. That win was the first of 547 races McCarron would win in 1974 in a whirlwind season that saw him set a record for races won and be voted the nation’s top apprentice.

Ghosts of racetracks past

For the mid-Atlantic tracks that did not survive, all we have left are grainy photos, yellowed programs and tattered tickets, fading mementos of a time when big crowds and great horses reigned supreme. Their stories:

“The horses handled the cold better than the people did”

Old-school Bowie logo.

Alfano was just 23 when he left trainer Dick Dutrow’s crew and struck out on his own. Despite the weather, he said, Bowie was still a good place to train.

“We never lost many training days back then,” he remembered. “They did a heckuva a job keeping the track open.”

Alfano was also quick to point out that just because they were racing in the winter didn’t mean the quality of the horses suffered. “It was tough racing in those days, really tough,” he said. “There wasn’t any racing in New York in those days and we would get a lot of outfits from there.”

It was during the early 70’s when Alfano made the claim that, as he put it, was his “springboard” horse, a filly named Cheerful Bragg. Alfano claimed Cheerful Bragg from King T. Leatherbury for $6250, moved her up the claiming ladder and into allowance company. He conditioned her to seven wins for owner Erwin Mendelson.

“She was the horse that kick-started my stable.” Alfano, who went on to win over 1,800 races, said of the daughter of Braxton Bragg.

Alfano said while winter racing wasn’t for the faint of heart, it wasn’t that bad, especially for the horses.

“The horses handled the cold a lot better than the people did,” he said with a chuckle. “We used to bed ‘em down deep, put their blankets on and close the doors at night, and they were fine. It was the people who were scrambling to stay warm.”

“A typical winter at Bowie”

He wasn’t lying about the people scrambling to stay warm.

I worked there in 1972. One February afternoon, the weather was clear and sunny through the first seven races. Just after the horses came out for the eighth, dark storm clouds swept across the sky and snow began to fall in buckets.

By the time the horses broke from the gate, it was snowing so hard that you couldn’t see the tote board from the press box.

Snow continued to come down heavily for several hours and quickly built up in the parking lots and surrounding roads. And the bridge with the only access to points north like Laurel was covered in snow and ice – making it impassable, and locking in those of us who lived north of the track.

It didn’t take long to realize that those of us who had had to finish our work before leaving weren’t going anywhere. After a few “brain dimmers” (cocktails) with Bowie’s legendary publicity director Muggins Feldman, the “orphans of the storm” were loaded into the track superintendent’s truck (which had four-wheel drive, a novelty in those days) and were driven to the Bowie Inn where the track treated us to dinner. Then we were brought back to the track where everyone found a bed, stretcher or couch in the first-aid room and spent the night.

With the “ice bridge” still impassable the next day, I spent much of the day in the track kitchen playing race horse rummy.

Just a typical winter at Bowie.

Entrance to Bowie in 2013. Photo by The Racing Biz.

“Hard-core horseplayers”

Located in the woods of Prince George’s County between Baltimore and Washington D.C, Bowie was one of three new thoroughbred tracks in Maryland to begin operation in a four-year period. (Laurel Race Track began running in 1911 and Havre De Grace kicked off its first meeting in 1912).

From the very first when the one-mile dirt oval ran its first race on October 14, 1914 and operated without a license for its first year of operation to be dubbed an “outlaw track,” Bowie had its own brand of fans and its own brand of racing.

“Bowie was an outpost,” Joe Kelly, respected writer and historian of Maryland racing, told the Baltimore Sun in 2010. “Going there was an adventure.”

A homely, no-frills plant, Bowie was a blue-collar kind of place. Horseplayers from up and down the East Coast flocked to Bowie, often coming by train. In 1961 a Pennsylvania Railroad race train derailed on a curve not far from the track, killing six racegoers and injuring 240 in the process.

Despite the tragedy, some horseplayers scrambled out of the wreckage and hurried to the track in 15-degree weather in an effort to get bets down on the first race on the card that afternoon.

Long time Maryland trainer King T. Leatherbury recalled, “I saw guys standing in line to bet with blood all over them. Now that’s what you call hard-core horseplayers.”

Horseplayers had a love affair with the “little track in the woods” and supported Bowie with a fervor rarely seen in the sport. On November 21, 1941, just weeks before the Pearl Harbor attack, some 30,000 fans thronged to Bowie, prompting this quote from a story in the Baltimore Sun.

“Sardines rest in roomy palaces compared to the 30,000 followers of the thoroughbred who squeezed their way into this race course… for the largest turnout in the track’s history.”

“A special spot in my heart”

And those fans got a chance to see some of the top horses and jockeys in the business. Conn McCready, Eddie Arcaro and Bill Shoemaker all rode at Bowie.

Bowie’s stakes program was highlighted by the John B. Campbell Handicap. Named for the noted racing secretary who assigned the imposts for the Experimental Free Handicap weights for a number of years, the Campbell typified the Bowie personality. It was a tough test for top handicap runners around two turns – it was run at distances from 1 1/16 miles to 1 ¼ — and it attracted some of the top stars in the sport.

Maryland-bred Hall of Famer Vertex counted the 1959 Campbell among his laurels. Yorktown won the 1962 edition of the Campbell, and the great Kelso won it the following year. In Reality also won the race, and in 1976 trainer Dickie Small sent out Festive Mood for the first of his four Campbell winners.

In 1981 Angel Cordero piloted the great mare Relaxing to victory. The Phipps star would be voted the top older Female runner in the sport that season.

Another stakes fixture was the Barbara Fritchie Handicap for fillies and mares, considered for many years as one of the top distaff sprints in the country. Top winners of the race included Tosmah (1966), First Bloom (1973), and the great Twixt, who teamed up with Bowie favorite Bill Passmore to take back to back editions in 1974-75. Skipat (1981), and Maryland star Mt. Airy Queen (1977) also were among the winners.

The track whose dedicated railbirds earned the sobriquet the “Bowie Breed” had its struggles, too. A series of fires over the years killed over 100 horses and caused untold amounts of property damage. And in 1975 four jockeys were convicted and sentenced to prison terms for fixing a race so that they could cash in on the track’s once-per-day trifecta.

By the 1980s, as winter racing became widespread, the track was scrambling to hold on. It closed for live racing in 1985, its grandstand taken down in 2004, but lived on as a training center, home to luminaries like Maryland-bred Hall of Famer Little Bold John and, in its last years, the Grade 1 winner Dance to Bristol. The training center closed in 2015, which appeared – at last – to be the end of the Bowie story.

Yet in a surprise twist, officials at the Maryland Jockey Club, which owns Bowie, revealed that they are considering re-opening it as what they say would be a “world-class” training facility.

McCarron, whose luminous career began at the track in the pines all those years ago, said he’s curious to see what happens next.

“I don’t know if they’re going to get that done, but I do know it would make a world-class training center,” McCarron said. “I know one thing: Bowie will always hold a special spot in my heart, and I was heartbroken the day it closed.”

Excellent!

Many great memories at Bowie. I was there when the last race was run, and also when they leveled the grandstand. It will be interesting to see what happens next.

Kudos to Doug McCoy for this wonderful story! Thru my years w/the MJC, starting in the 90’s, I’ve been intrigued w/all the Bowie memories via press box denizens, stewards (especially Bill Passmore), trainers like Charlie H. Hadry, John Lenzini, & several riders – – among others. I was fortunate to work both front-side & back-side, so my sources had varied perspectives – – but ALL spoke of Bowie as if I’d missed the Best of MD racing!

I used to drive standbred horses. In the

winter of ’75 we were racing at Brandywine Raceway. When we would get cancelled cause of weather, a few of

us horseman would get together & go

to Bowie. Through contacts we meant, we got to talk to a few trainers & jocks

agents. Very interesting & informative

people. Supposed to go the day of the

so-called bad race, but changed our

mind. Learned alot from the people I

did meet.

Muggins Feldman was an ace.

Met him in the Garden State Park press box playing gin rummy against Morris Toby and Jonas Comisky

I live near Bowie, but I never got to go, since it closed down right when I started to get into racing. I hope they fix it up nice and make it perfect for the horses.

Excellent article! Be sure to keep us updated. 🙂

First time I was leading rider in “69” with the bug. Howard Jello Hall was my agent; he was the Best!!! A lot of fond memories there! Very Cold but we did it!