Argyle and Thoroughbred racing in the 1830s

By Donald Walsh

On April 11, 1830, a bay colt who would become one of the fastest thoroughbreds in the United States was foaled at Maryland’s Marietta plantation.

He was out of the mare Thistle, owned by Edmund Brice Duval, son of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Gabriel Duvall (note: the spelling of Duval/Duvall is consistent with the usage at Marietta Museum and other sources). Gabriel Duvall was also a racing historian, and he had Marietta built in Prince George’s County in 1816. Marietta House still stands and is currently a museum.

In 1829 Edmund sent Thistle to Virginia to be covered by the successful racehorse and sire Monsieur Tonson. He named the colt that resulted from this mating Argyle.

Beset by physical and mental illnesses which resulted in his untimely death in Philadelphia in 1831, Edmund would not see Argyle reach the races. Justice Duvall, as executor of his son’s estate, sold the horse for $500 to Pierce Mason Butler of South Carolina.

Butler was married to Gabriel’s niece Miranda, whom he met while serving in the Army at Fort Gibson in the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). Butler also wanted to purchase Thistle, but Duvall had promised her to his cousin George Washington Duvall, who bred thoroughbreds at his estate Prospect Hill, about a mile north of Marietta. (The manor at Prospect Hill was the clubhouse of Glenn Dale Golf Club until it closed in 2019.)

Argyle’s first race was on January 3, 1834, in Orangeburg, South Carolina. During this period, thoroughbreds turned a year older on May 1, (instead of January 1 as they do today) so Argyle was still considered a three-year-old. Racing before the Civil War was conducted in heats of one, two, three, or four miles. The distance of a race depended on the age and quality of the horses. The best horses ran heats of four miles. The first horse to win two heats would be declared the winner. There was a 30-minute cool down period between heats. In his debut, Argyle defeated a 5-year old mare named Fanny by winning the first two heats of two miles each.

Over the next thirteen months, Argyle would race four more times, in heats of either three or four miles. He won each race without losing a single heat. By the spring of 1835, he was a four-year-old of considerable reputation, having won his last two races over the renowned Washington Course in Charleston, and earning over $3,500 in purses. With his undefeated horse, Butler looked to run Argyle in a match race, where the greatest amount of fame and fortune could be won.

A match race was a contest arranged by the owners (rather than racetrack proprietors), where one owner would challenge another, often for stakes of $5,000 a side, sometimes $10,000 or more. The most celebrated of these races often pitted a northern horse against a southern horse, with the winners touted as proof that one region had superior racing stock and breeders. The biggest such race took place in 1823 at the Union Course on Long Island, New York, where over 50,000 spectators watched the northern horse American Eclipse defeat the southern horse, Henry. American Eclipse won the second and third heats despite having lost the first heat in which Henry set a new record for the fastest four-mile time.

LISTEN TO THE LATEST OFF TO THE RACES RADIO!

Match race challenges were made in one of the sporting periodicals of the time: the American Turf Register and Sporting Magazine, published by John S. Skinner of Baltimore, or The Spirit of the Times, published by William T. Porter out of New York. In the fall of 1834, John C. Craig, of Philadelphia, had issued an open challenge to run his horse, Shark, against any horse for $10,000 a side, to be contested at either the Union Course or the Central Course (in Baltimore). If the challenge was not accepted by the start of 1835, then Shark would cover up to 20 mares at a stud fee of $100.

Butler, backed by a syndicate, “the friends [sic] of Argyle”, attempted to re-ignite the prospect of a match versus Shark the following March. He offered to run Argyle against Shark for either $5,000 or $10,000 a side with the race to be held in either Columbia or Charleston in South Carolina. Like Shark, Argyle would also cover mares in the spring of 1835. The practice of covering mares while still racing was not uncommon for the period.

The match race with Shark would never materialize, however, and at some time during that year, Butler sold a portion of Argyle to James Henry Hammond.

Hammond was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from South Carolina. Like Butler, he would go on to become Governor of that state. Hammond, fiercely pro-slavery, put forth the “mudsill theory,” which claimed that there must be a permanent lower class for the upper class of society to rest upon. He would also become infamous in 1843 for sexually abusing his four teenage nieces.

Argyle returned to the races in December of 1835, in Columbia. He won the first heat, after which his lone opponent was withdrawn from the race. Soon thereafter, Butler and Hammond sold two-thirds interest of Argyle to Wade Hampton II and William Ransom Johnson, for $10,000. With a combined valuation of $15,000, Argyle was one of the most valuable horses in America, worth thirty times what Butler had paid for him four years ago.

Wade Hampton was a former South Carolina state senator from a wealthy plantation family. He was Hammond’s brother-in-law, and father of the four daughters that Hammond would later be accused of molesting. Johnson was the most famous horseman of the day, dubbed “The Napoleon of the Turf.” He owned the great Sir Archy, the foundation sire of the South. He brought Henry up to the match race versus American Eclipse in 1823. He was the architect of some of the biggest match races across America, and he sought an opportunity to arrange such a race for Argyle.

The match he arranged was to be run on April 12, 1836, at the Lafayette Course in Augusta, Georgia. The opposing owner, Col. John Crowell, could name any one of four of his best horses at the time of post. Hampton and Johnson staked $17,000 against Crowell’s $15,000. Crowell eventually selected his four-year-old colt John Bascombe to be Argyle’s opponent. Unfortunately, Argyle was injured a few days before the race when a cheekpiece on his bit pierced the roof of his mouth, causing him to lose as much as two quarts of blood.

But his connections made the decision to soldier on.

The race was an event of local, regional, and national significance. In The Spirit of the Times, it was reported that “there never were as many persons assembled probably on any race Course in the South… The population of our City is about 8,000, and I really think that 5,000 people were witnesses to the above race.”

The overall amount of wagers placed on the contest was staggering: reportedly from $200,000 to $500,000.

But the race itself was anticlimactic. Likely as a result of his injury, Argyle was distanced by John Bascombe in the first heat.

The distance rule prevented a horse and jockey from giving up in a heat in order to conserve energy for later heats. Any horse not past the distance flag (placed 150-250 yards from the finish line, depending on the track) when the winner reached the finish line would be disqualified from the race.

Argyle’s subpar outing does not detract from John Bascombe’s race, though. The winner’s time for the heat was 7 minutes, 44 seconds, the fastest since Henry in 1823 (7 minutes, 37 seconds).

John Bascombe, following his victory, gained even more fame by traveling up to New York, under the care of his new manager, William Ransom Johnson. John Bascombe made headlines again, winning glory for the South by defeating the northern champion, Post Boy (foaled in New York in 1831, not to be confused with Ridgeley’s Post Boy, foaled in Maryland in 1800), at the Union Course on May 31, 1836, for $5,000 a side, in front of 20,000 spectators.

Fading from the spotlight, Argyle eventually returned and lost his next race in the fall of 1836. Still in the stable of Johnson, Argyle raced primarily in Virginia and Maryland. The following year at six he won at Broad Rock and at the famed Newmarket course in Petersburg.

In May, having turned seven, he lost over the Central Course in Baltimore in a race where he threw the first heat (finishing fourth while conserving energy but also avoiding being distanced) then won the second heat before finishing a close second in the last two heats to the winning mare Camsidell. This was regarded as “the best contested race which ever took place over the Central Course.”

Argyle won one of his two remaining races in 1837, but did not run at all in 1838, presumably due to hoof issues. “Nothing but his bad feet,” remarked Col. Johnson, “prevented his being one of the most distinguished racers of his day.” Nevertheless, Argyle returned to the track in April 1839, winning at the Newmarket Course in Petersburg.

The next month, on May 16, at the Kendall Course in Baltimore (located in Canton), Argyle, having just turned nine years old, ran a race that brought him back into the national spotlight.

Argyle finished second to Wonder in the first heat. In the second heat, in the time of 5 minutes, 40 seconds, Argyle broke the three-mile record. The three-mile record was the second most important record in American sports, behind the four-mile record, and Argyle broke it as a nine-year-old. Also remarkable is that the second heat was run seven and a half seconds faster than the first.

But after running so quickly over the first six miles, Argyle finished behind the eventual winner Master Henry in the third and fourth heats. This race and Argyle’s time would be recollected for many years to come.

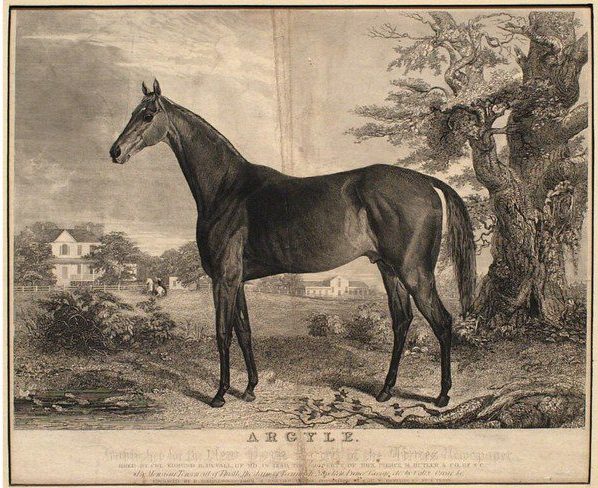

In the fall of 1839, Argyle would win one last race at Broad Rock, Virginia, before Johnson brought him north to New Jersey, where he lost his final two races and was retired from racing. Because to his fame, The Spirit of the Times included Argyle in a set of engravings available at a premium to subscribers in the 1840s and 1850s. Other famous thoroughbreds in that set of engravings were Boston, John Bascombe, Fashion, and Black Maria.

In retirement, Argyle returned to Pierce Mason Butler, who had served as Governor of South Carolina from 1836 until 1838. After his term as Governor, Butler was appointed an Agent to the Cherokee Nation at Fort Gibson, where he had served in the Army twenty years before. Along with Butler, Argyle made the trip west to the Indian Territory. An advertisement for his stallion services appears in the Arkansas Intelligencer in April of 1845, where he stood at the plantation of Samuel Mays (Mayes).

In 1846, Butler was appointed Colonel of the Palmetto Regiment, a unit of South Carolinian soldiers who fought in the Mexican-American War. Butler was killed on August 27, 1847, at the Battle of Churubusco near Mexico City. After his death, his estate was settled by his wife’s family, members of the Duval family living in Van Buren, Arkansas.

Argyle’s life had come full circle, although his story continues on a bit further. Eighteen years after being sold by Gabriel Duvall to Pierce Mason Butler, he was sold again by the Duval family at auction on January 1, 1850.

In March of 1853, the following ad appeared in The Standard (Clarksville, TX). Argyle would have been 22 years old. Results for races in Texas show that Argyle covered mares until at least 1856. As a stud, he was not a notable success, his best progeny being Governor Butler (out of Mary Frances by Director) and Kate Seyton (out of Pocahontas by Sir Archy), both winners and both from his time at stud in 1835.

On the track, Argyle was a winner of his first six races without losing a single heat. He set a new three-mile record as a nine-year-old. His career in summary: 19 races, 12 wins, $7,100 in purse earnings. Certainly, he is one of the greatest Maryland-breds of the nineteenth century, and he deserves consideration as one of the greatest Maryland-breds ever.

Selected Sources:

Argyle. (2024, December 3). In Pedigree Online Thoroughbred Database. https://www.pedigreequery.com/argyle3

“The Celebrated Race Horse and Stallion Argyle.” The Arkansas Intelligencer, Van Buren, AR, Mar. 29, 1845.

“Administrator’s Sale.” The Arkansas Intelligencer, Van Buren, AR, Nov. 24, 1849.

“Races! Races!” Dallas Weekly Herald, Dallas, TX, Oct. 19, 1859.

“Duval, Edmund Brice, biographical information”, Vertical File, Marietta Museum, Prince George’s County, Maryland

Moseman, C.M. and Brother, Moseman’s Illustrated Guide for Purchasers of Horse Furnishing Goods, Novelties, and Stable Appointments, Imported and Domestic: For the Wholesale and Retail Trade, 5th Edition (undated), E.D Croker and Sun, New York. p.130.

Newman, H. Wright. (1952). Mareen Duvall of Middle Plantation: a genealogical history of Mareen Duvall, Gent., of the Province of Maryland and his descendants, with histories of the allied families of Tyler, Clarke, Poole, Hall, and Merriken. Washington.

Porter, William T. (ed.) The Spirit of the Times. (Vols 4-20) New York, NY. William T. Porter

Porter, William T. (ed.) “Memoir of Argyle.” American Turf Register and Sporting Magazine , Vol. 14, August, 1943, New York, NY. William T. Porter. pp. 431-6.

Richards, M. (2016, May 17). Butler, Pierce Mason. South Carolina Encyclopedia. https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/butler-pierce-mason/

Skinner, J. S., et. al. (ed.) American Turf Register and Sporting Magazine. (Vols 5-15) Baltimore, MD. J. S. Skinner

“Argyle.” The Standard, Clarksville, TX. Mar. 19, 1853.

Pierce Mason Butler. (2024, December 23). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pierce_Mason_Butler James H. Hammond. (2025, February 21). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_H._Hammond

LATEST NEWS